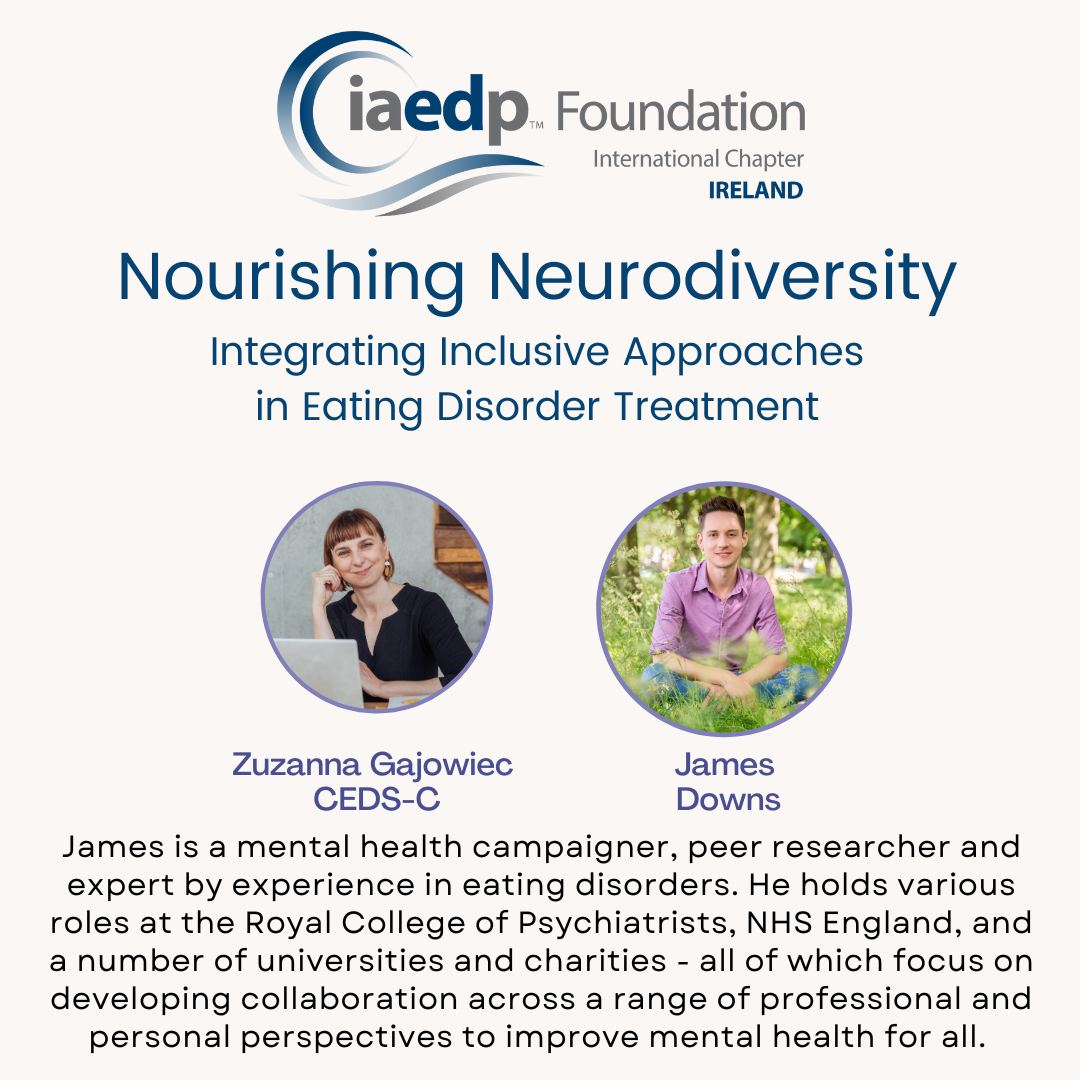

“Help that helps vs Help that hurts-Part 2,” Zuzanna Gajowiec in conversation with James Downs

Lived experience and a professional’s perspective on eating disorder treatment of neurodiverse populations.

Zuzanna Gajowiec, CEDS-C in conversation with James Downs.

Treating and caring for individuals who are neurodiverse and struggle with an eating disorder presents unique and complex challenges. The title of this article, and an expression I learned from Dr. Karen Samuels (CEDS), fits so well. As professionals, we have good intentions and try our best, yet still, unintentionally can cause harm. The eating disorder field is one of the most challenging in mental health, because eating disorder recovery combines physical and psychological risks. In addition, as a relatively new field, it also offers limited research and resources to guide us. This is also a field of very passionate and dedicated clinicians, eager to learn. Eager to do no harm.

This is a second part of a series of articles created to help professionals become more aware of the needs of our clients in treatment for an eating disorder with both diagnosed, and undiagnosed, neurodiversity. It is so important to include the “not yet diagnosed” population into the conversation because symptoms of eating disorders can be overshadowed by neurodiverse conditions and vice versa, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. There are also many barriers to assessment and diagnosis: money, long waiting lists, availability, shortage of trained providers, tendency for masking by neurodiverse individuals and professionals’ biases.

In this article, I am so excited to interview James Downs, a fierce advocate, researcher and contributor to the development of MEED guidelines. He is an incredibly important voice in our field. I first met James at the Irish Eating Disorder Conference in Dublin, Ireland and have followed his work ever since. James’ papers focus on lived experience and advocacy for equitable mental healthcare and inclusivity, with a specific focus on eating disorders.

ZG: Zuzanna Gajowiec (ZG): I am a Clinical Psychologist and Family Therapist, Certified Eating Disorder Specialist and Consultant (CEDS-C). Welcome James, could you introduce yourself and tell us about your work.

JD: My name is James Downs, and like many of us, I have lots of different roles and identities that I move between in my life. One of those is as someone with lived experience of eating disorders and other co-occurring health conditions. I’m also neurodivergent and found out in my 30s that I am autistic and have ADHD. While I would have loved to have known about this sooner, it has been incredibly important for me to have a better understanding of myself and my differences and to recognize that they are not personal defects or things to be erased. As I move further into my recovery than ever before, I can see that a big part of my progress has been in allowing myself to be truly myself, without trying to pretend or fit into an image of what I think I should be like.

ZG: Thank you for sharing that. I hear this a lot (sadly). People with eating disorders are only being diagnosed with Autism or ADHD in adulthood and feel that if they had known this earlier, their recovery would have looked different. It is usually an important “piece of the puzzle” for people, but sometimes even having this diagnosis does not guarantee appropriate care.

What would you like to share about your experience of seeking help and your journey of eating disorder recovery so far?

JD: When it comes to the help I have sought when I have been unwell over the years, the theme of fitting in or not fitting in—is a common thread throughout my experiences. There have been many times when I haven’t met the criteria for particular services, leaving me without any help at all. I think we sometimes overlook the impact of being completely excluded from the support we need. Reminding myself that neglect is a form of abuse has helped me respond more compassionately to how I have felt when I’ve had to struggle with profound suffering entirely on my own.

ZG: I am so sorry to hear this and I am also grateful you so openly share, both in your presentations and in the published papers, what so many people suffering with an eating disorder experience. There are so many barriers to accessing treatment. It is horrible that often people need to advocate for themselves or have to prove in some way that they are sick enough or “worthy” of access to particular treatments. And even after accessing this treatment, it is not always helpful…

JD: When I have been able to access treatment, it has often been unhelpful because it imposed ideas upon me that simply don’t fit. I have been frustrated by how many assumptions people have made about me based on superficial appearances. For example, I have often been denied important medical investigations because I appeared to be well, which doesn’t fit the stereotype of someone with an eating disorder. This has actually been very dangerous because I have had extremely high-risk problems that went undetected until it was almost too late.

I’ve also felt like I have to change myself to fit certain stereotypes. The driving factors behind my eating disorder symptoms were never really in line with those in the treatment models and patient materials I received. These resources often used female pronouns, making me feel completely unrepresented.

After a while, I stopped trying to communicate my real concerns and began to perform elements of illness that I never exhibited when I entered services. I felt that in order to be understood and taken seriously as a patient with anorexia, I had to perform in a particular way and exhibit the features of illness that were expected. This led to a host of other problems and was ultimately very harmful.

It has also been difficult to participate in treatment systems and organizations that have been really confusing and exclusionary to me as an autistic person. I’ve found that the burden is too great on the patient to jump through many hoops and overcome significant barriers to get into the treatment room in the first place.

ZG: It seems like the title of this article is indeed very accurate and the places we go for help can often harm… tell us more about the challenges.

JD: The challenges I face include having to use the telephone at unpredictable times, needing to opt in to demonstrate my motivation for treatment before being placed on a waiting list, and struggling to comprehend patient information that is simply unclear to me. When I have asked for clarification or raised concerns about my experiences, I have often been met with extreme defensiveness and a lack of willingness to learn about how treatment could become more inclusive and reduce the burden on patients like me.

That said, even my negative experiences of not feeling helped in the way I should have been give me cause for hope. It is very easy to envision how things could be better for patients like me, if those seeking to help us more effectively take time to listen to our experiences rather than defend the status quo.

ZG: You are so clear in your presentations and papers about that: how things should be improved, and how services should be run to not harm and not discriminate. I have read your work and have had the pleasure of listening to you a number of times. Could you give us some examples here for people reading this article?

JD. Yes, so for example, I have also had very helpful experiences of treatment, where I felt respected and met with an understanding of myself as I am, rather than as I am expected to be. Fundamentally, being someone you are not is no basis for therapeutic change or for establishing a collaborative relationship with the person who is there to help you. When I finally started recovering, it was within the context of a truly authentic relationship with a therapist who did not judge me for my difficulties and accepted my differences rather than rejecting them. Having the space to create shared understandings has also been vitally important, rather than having explanations imposed upon me that don’t fit.

One of the most helpful things for me, especially as someone who has had difficult experiences with treatment in the past, has been the acknowledgment that my difficulties related to that are not my fault. I do not need my treatment providers to feel blamed or take personal responsibility for the harm I have encountered in the past, but I do want them to accept that it is real for me and to respond with this in mind. It is entirely natural to feel ambivalent about returning to treatment when it has been harmful in the past, but ignoring this reality is not going to help.

ZG: In my professional experience I have often seen two, I believe not so helpful reactions from professionals. And to me, it feels like both are from the same category of “brushing things off”. The first one is to feel somewhat uncomfortable with the conversation about previous harm and ignoring it. The second is overpromising that this type of harm will never happen here. In other words, making the complaint sound like an exception.

Again, as we said in the intro – clinicians usually don’t want to cause harm, but often unfortunately they do.

I think it would be great to really listen and reflect on our services and not overpromise, because the harm is more of a systemic problem, rather than individual – for example we can offer great care in outpatient services, but clients can still be dismissed in hospitals etc. What would you say the right response could look like?

JD: Recently, I returned to treatment and felt that my past difficulties were truly respected, and the team wanted to do everything they could to help me avoid encountering the same issues again. By bringing these challenges into the open without judgements or fear of being blamed, we have been able to establish meaningful, mutually respectful relationships. When I have raised concerns about my treatment with them, instead of feeling blamed and marginalized, the team has been open to learning from my feedback, which has been a restorative experience for me and has helped me trust them in the future.

Ultimately, I think that much more could be done to make the help that people need more inclusive and acceptable. Just because support is available in theory does not mean that it is accessible, and difficulties in accessing services need to be addressed by those providing them, not by those who are already unwell and struggling against the odds to ask for help.

ZG: Exactly. We often charge people who already struggle, such as people with eating disorders or their parents, to advocate and even campaign for equitable services. This is so wrong.

I also know so many professionals who are also feeling overwhelmed by the lack of support (for example nowhere to refer on to, hospitals dismissing clients in need, lack of specialized treatments.) So how can we change this?

JD: Achieving this will require a cultural change, where treatment providers become more curious about their own role in upholding exclusion and poor outcomes for people who are different. There is nothing to fear about becoming more inclusive. There is no slippery slope, and those like me are not demanding special treatment. In fact, making help more effective and less harmful for those who diverge from the norm benefits everyone—patients and clinicians alike.

ZG: So beautifully put. Thank you so much James.

You can learn more about James’ publications here:

We have both presented at the Irish iaedp™ chapter CONFERENCE “Nourishing Neurodiversity: Integrating Inclusive Approaches in Eating Disorder Treatment” Integrating Inclusive Approaches in Eating Disorder Treatment” organized by Chapter Chair Zuzanna Gajowiec CEDS-C